Warden’s Blog – Righting the Wrongs of the Past

If you were not too distracted by the hysteria surrounding the announcement of the European Super League – thank goodness that plan is off the table – you may have been following the verdict following the trial of the police officer who killed George Floyd. I am sure that the whole world breathed a sigh of relief when the verdict was announced and we all hope and pray that it represents a new era in policing and racial justice in the United States.

I was interested this morning to read another headline on the BBC News website, with more encouraging steps to right some of the wrongs of the past. The British have always looked after the cemeteries of their First World War dead very well and they are very moving to visit. However, it transpires that non-white soldiers fighting for the British were never given their own headstones, but were merely listed on memorials, or in documents, or not at all. The actual graves of most are not known. As shocking as it is to our modern sensibilities, it was thought that ‘the average native…would not understand or appreciate a headstone.’ Thus the contribution of thousands of colonial troops to the British war effort has never been properly recognised.

An inquiry has reported that an estimated 50,000 Asian and African troops, who died in the conflict, were ‘commemorated unequally.’ There are now plans afoot to set this record straight and, although I don’t know the form that this will take, it is surely very positive that authorities are not saying merely, ‘let’s make sure we get this right in the future,’ but ‘let’s put right an historic wrong now, albeit 100 years too late.’

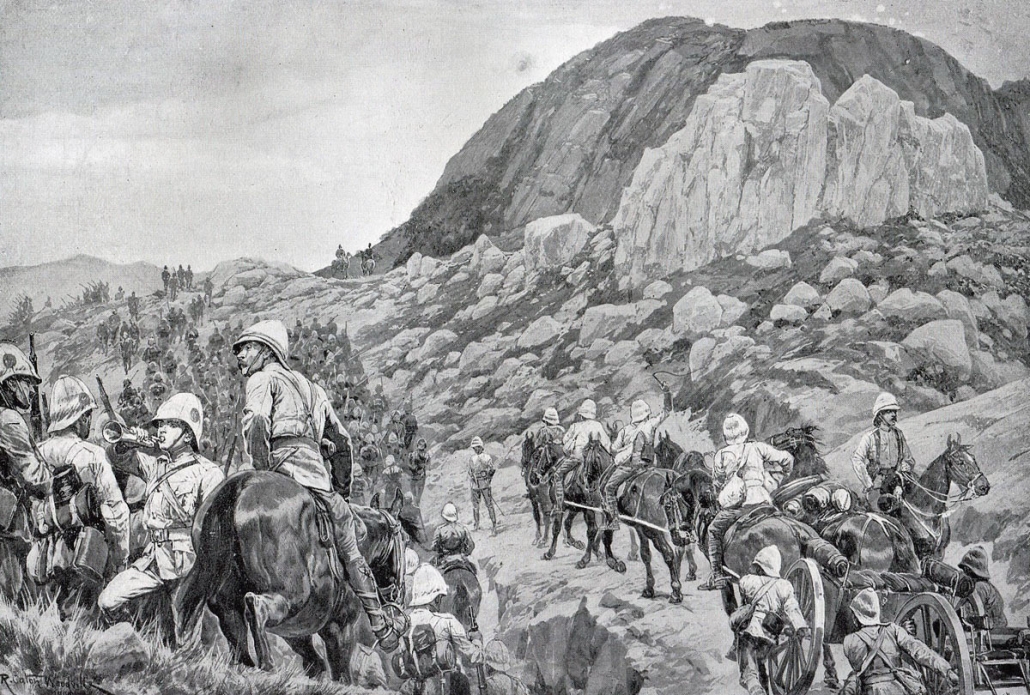

It reminds me very much of a trip I made in my last few months in South Africa in 2016, when I visited the historic battlefields of the Zulu War of 1879 and the Boer War, which pitched the British against the Afrikaaners from 1899-1902. At the time these wars captured the imagination of the British public like no other and tales of derring-do were eagerly reported in the British press. Now we are rather embarrassed by it all, although it is a fascinating period of history. My first visit was to Spion Kop, a major battle of the Boer War, as well as an embarrassing British defeat. On a rocky hilltop hundreds of troops from Liverpool were mown down, but their heroism was commemorated in the naming of a new stand at Anfield, the ground of Liverpool Football Club, which, because it was steep and high, was given the name the Spion Kop. As a Liverpool supporter I felt that I was making a pilgrimage.

However, the point of my story is this. On top of this rugged and distant outcrop soon afterwards the British, ever keen to celebrate their heroes, put up memorials to those who had died from their Liverpool regiments. They are all listed and it is moving. However, what was forgotten and not acknowledged was that these white soldiers were supported by large numbers of Indians acting as stretcher bearers and water carriers. Many of them died, but there was no memorial to them. The honest, tough Liverpool soldiers received a fitting monument, but perhaps it was not considered that these Indians would have ‘understood or appreciated’ such a memorial. Or perhaps worse, it was thought quite simply that the life of an Indian was not worth as much as a white man and that it would have insulted the soldiers to commemorate the Indians in a like manner.

Anyway, whatever the original thinking was, it was fitting that fairly recently (within the last 20 years or so) this wrong was put right and there does now exist a memorial to those Indians who died at Spion Kop and a tribute to the bravery of all the Indians who were involved, including, remarkably, a young stretcher-bearer called Mohandas K. Gandhi. Incidentally Winston Churchill was also there, working as a journalist. It is extraordinary that two of the giants of the 20th century were present at what was, in the bigger scheme of things, a minor skirmish.

It is never too late to right the wrongs of the past. The conviction of a police officer doesn’t change the past, but it does send a message to the future. And the building of memorials, even at a much later date, does also help to address the prejudices of the past and help us to look forward to a better and more just future.